The innovative hotbed of artistic production that was EC Comics in the early 1950s certainly nurtured several of the most distinctive comic artists. Many of the publisher’s favored contributors from Jack Davis, to Al Williamson, to Graham Ingels, to Johnny Craig work in singular modes that are all immediately recognizable as distinctive and unique. The same, too, could be said of the work of John Severin, another EC worker whose art bespeaks of a favored set of representational practices, in short an individual visual system. However, how can one go about defining individual visual styles in an under-theorized artistic practice like comic art; what does it mean to isolate some artists and not others; and what variable as are the most pertinent to such an analysis?

In early film studies of the auteurist mode, critics often explicitly and implicitly segregated directors into categories of those merely working in and through house styles and those who push beyond these representational systems. Mainstream comics workers could certainly be sorted out in a similar manner as a publisher like Marvel employed artists ranging from Don Heck, Herb Trimpe and Sal Buscema — all fine artists, but largely practioners of a familiar superhero house style grounded in the work of Jack Kirby — from Jim Starlin and Jim Steranko — two artists whose works is unmistakably their own and distinct.

What this parsing out, however, neglects is the establishment of a clear set of categories we can use to distinguish one comic artist from the next. In the remainder of this post, I will consider what makes John Severin’s art so immediately distinct and consider how this suggest a set of analytic variables to consider individual visuals systems and set them against one another in comparative analysis.

Probably the most apparent, but also the weakest variable to consider is that of subject matter: what types of narratives and subjects does the artist tend to gravitate towards. Of course, the ability of a mainstream artist to choose his subjects can be limited. But, on the other hand, editorial mechanisms and personal choice certainly lead artists to play to their strengths. In the case of Severin, the artist describes, in this career-spanning interview with Gary Groth, his EC editor Harvey Kurtzman’s insistence on picking out drawing assignments for Severin based what the editor saw as the artist’s innate strengths. His EC work then is focused on war and western action where the clarity of his line work, his attention to accurate detail and his expertise in crowded compositions were put to excellent use. Conversely, Severin and his editors avoided assignments where he was asked to invent “unrealistic” images (he rarely worked on EC’s horror and science fiction books) and depict glamorous women (he rarely worked on EC’s crime and thriller books — Severin, himself, has stated, “I had no interest in drawing pretty girls. I’d rather draw a horse”). Defined by its preferred subject matter, Severin’s visual world is a deeply Hawksian one depicting the world of professional men in an equal mix of war stories (Two-Fisted Action), westerns (American Eagle), fantasy (King Kull) and comedies (Severin contributed to the humor magazine Cracked for almost its entire fifty year run).

However, to more closely decipher an artist’s visual system we must move past the manifest subject matter and dissect the repeated tendencies in the drawing itself. Specifically, comic art, a deeply narrative art, depends more or less on the combination of attitudes toward at least three graphic variables: detail of figures and objects, figural shape, and composition, that is, the placement of detail and figure in represented space. We can describe Severin’s unique attitude towards these questions of comic form, just as one could of any accomplished comic artist and arrive at slightly different or drastically different matrix of choices and strategies.

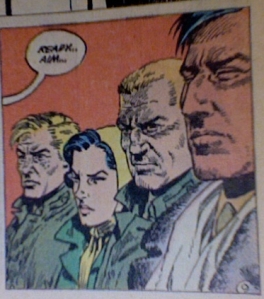

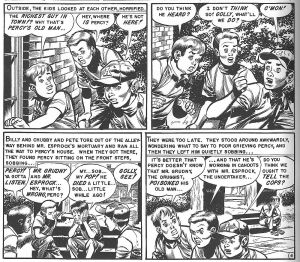

We have already described Severin as an artist deeply interested in accuracy and fidelity of detail. This concern was informed by the artist’s disposition — Severin was a self-described history buff, genuinely concerned with accuracy for its own sake — and his technique — Severin preferred the use of pen over the more painterly use of the brushing in inking, allowing for a more precise, less painterly result closer to mechanical drawing than fine art. But probably the most important and distinctive use of detail in comic art has to do with the artist’s rendering of the human face and their portraiture style. Comic artists often develop distinctive techniques to depict the human face, a vitally important image for most comic narratives. In interview, Severin has referred to his own inability to drawn apart from reality and his commitment to draw human faces as if taken from the man on the street. However, this only gets partly to the truth of his drafting. Severin clearly adds to and participates in a certain tradition of facial cartooning that favors the use certain shorthands (eyes as horizontal lines, jaws wide and square) to depict masculine power. Here graphic tendencies underscore the Hawksian subject matter of masterful men at serious work (and lampooned in the same depictions made laughable in his humor publications).

– From The Losers #141

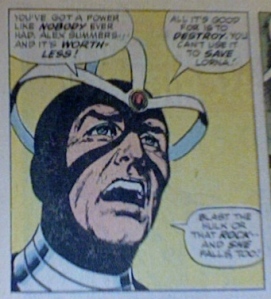

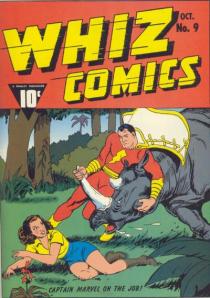

– From Whiz Comics #9, one of the earliest, most important uses of this visual shorthand was probably C.C. Beck’s Captain Marvel…

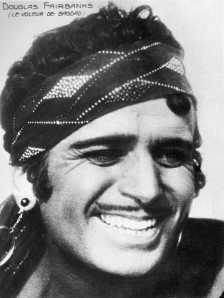

…which was probably a graphic structural equivalent of the actual face of Douglas Fairbanks…

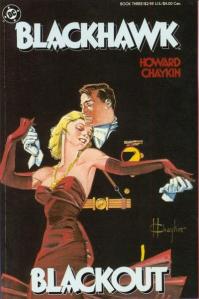

…and whose graphic and thematic tradition is maintain most clearly by artist Howard Chaykin

Moreover, Severin’s depiction of faces again marks him an artist whose base constituent element is always the short, hatched pen line. This puts his in sharp distinction with his EC contemporaries like Jack Davis who builds his faces up from curved strokes…

…and Graham Ingels who builds facial detail with irregular, multidirectional and thick brushstrokes.

We can also isolate individual visual systems in comic art by considering the typical methods used to depict human form in its entirety. Although Severin’s work is comprised of men in violent or humorous action, his depiction of the human form stands apart from the Marvel Kirby-Ditko school of maximizing a body’s contortion and skew with respect to the panel. In other words, Severin’s bodies avoid the absurd figural ballet typical of classical superhero drawing. Incidentally, this is what makes his work with Trimpe on the silver-age Hulk so odd, but also so dynamic as Severin who adds volume and human emotion to the penciller’s work, which at that point was more or less still lifts from classic Kirby panels.

– from Incredible Hulk #150

– from Incredible Hulk #150

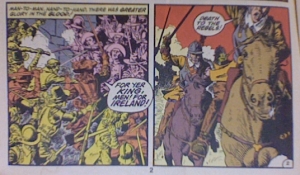

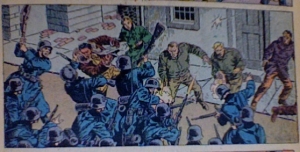

Look for example at a series of panels from Severin’s “The Pike.” Here the soldiers are fighting for their lives; however, none of the individual bodies are stretched in a manner that begs credulity and the panels aren’t emphatically tilted and distorted to artificially inflate drama — yet all the same the violence and desperation are transmitted all be they in “human” and not “superhuman” terms.

– From Amazing High Adventures #1

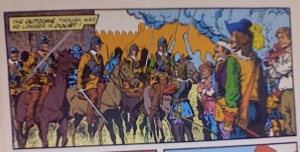

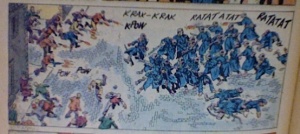

And lastly we can consider the distinct way in which comic artists build their individual visual systems through their repeated decisions and strategies with regards to composition. In the case of Severin, his devotion to clarity and detail inform his overall method, leading him in uncharacteristic distant shots to depict intense action…

– From The Losers #141

– From Amazing High Adventures #1

– From The Losers #149

…as well as frontally as the most telling vantage and placement of figures.

As Severin states in his Groth interview his preference for depicting action “straight on.” It’s hard not to read into the artist’s rather unglamorous, but truthful depiction of violence and action, coming from someone schooled in the decidedly anti-war Kurtzman books and from someone who saw the horrors of war firsthand in the Pacific. But ultimately, I believe Severin’s visual system was mostly dedicated to his commitment to clarity above all else, again putting the artist alongside his filmmaker analogue Hawks who likewise seems to pride himself chiefly in the ability to find the most telling image from the narrative or performance. Severin’s system of building detail, arranging forms and putting them in space is ultimately concerned, too, with maximizing clarity, but doing so in a way that confounded many of the already established patterns of comic form, particularly with regards to the already calcifying grammar of comic action.

To end with the words of Severin on precisely this point: “there are methods: faces, embraces, hero types, poses even…although I may have used every one of these things at one time or another, in general I sort of—let’s say I went my own way.”